The First Time I Read Elmore Leonard

It was In an ad in Hot Rod Magazine for Hurst Floor Shifters

The First Time I Read Elmore Leonard

It Was in Hot Rod Magazine in an ad for Hurst Shifters

George Hurst was a machinist from Pennsylvania, born in 1927, a classic postwar hot rod kid who turned his fascination with speed into a career. He started out machining engine mounts in a little shop in Warminster, PA. By the late 1950s, he’d teamed up with Bill Campbell to form Hurst-Campbell, in the business of making serious performance gear.

George saw that most cars — even so-called factory muscle cars — had lousy shifters, prone to missing gears when you jammed them hard. So George built his own, designed to take abuse. By the early 1960s, Hurst shifters were being installed at the factory and the dealership on cars from Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Plymouth, Dodge, AMC, and Buick. No longer just an aftermarket hot rod part, if your car had a Hurst shifter, that was a sign you were serious — whether you were on the strip or revving at a red light.

George made the connection between automotive performance and theater. He built a legend around his shifter.

He poured money and energy into sponsorships, exhibition cars, and publicity stunts. He’d show up at drag strips all over the country with the Hurst truck, packed with mechanics and engineers in crisp shirts and lab coats, ready to fix racers’ linkages and diagnose problems for free.

Then there was Linda Vaughn — Miss Hurst Golden Shifter. With her towering blonde hair and statuesque figure, hoisting an oversized chrome Hurst stick over her shoulder, she became a drag strip legend. Fans came to see the races, but they also came to see Linda, to pose next to her, get a signed photo.

There were show cars that George developed. The most famous, the Hurst Hemi Under Glass, a Plymouth Barracuda with a 426 Hemi literally in the back seat, which would do wheel stands for the length of the track; all four wheels sometimes off the ground.

As for advertising, George needed a writer who didn’t just list specs, but had a distinctive sound and attitude. That’s where Dutch came in.

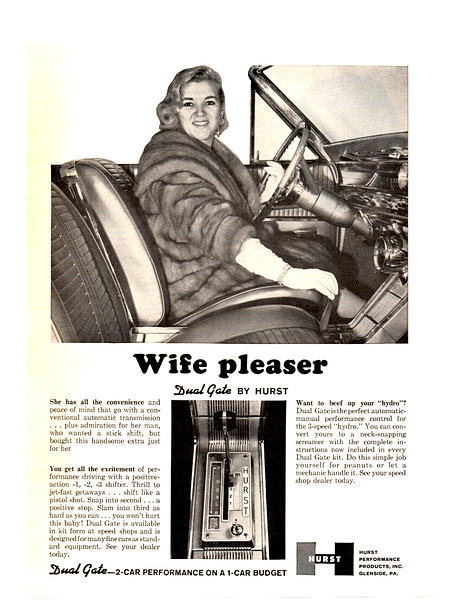

Dutch was in his late 30s in the early 1960s. He had recently left Campbell-Ewald, the Detroit ad agency where he’d written Chevy ads. He had hoped to be able to write novels full time, but with four kids and a new house in Birmingham, Michigan, reality set in. So he freelanced. A lot. Somewhere around 1962 or ’63, he hooked up with George Hurst, then, working with an art director named Bob Rogers, come up with an ad concept over lunch — often with little more direction than “make it tough, make it funny, make it sell” — then Rogers would shoot the photo later that day. “George would fly into Detroit once a month,” Dutch told me, “look over the proofs, nod, and off it would go to car magazines, including Hot Rod Magazine, Motor Trend, Super Stock, and Car and Driver.”

Dutch didn’t know a thing about drag racing when he started. Or shifters, or torque multiplication, or why someone would want to move a car’s rear axle forward 10 inches. But he learned fast, picked up the words, and did what he did in his fiction — adopted a character’s point of view.

“Get a fistful of authority.”

“The company best known for 4 on the floor is now pulling 4 off the ground… and shifting in mid air!”

“Guaranteed for life — unless stepped on by an 8-ton East African bull elephant from the Tanganyika Game Preserve while your wife or girl friend is driving the car.”

You can clearly hear Dutch’s sound and outsider attitude in those Hurst ads. There was no corny sloganizing. They were cocky. They teased you. They dared you to blow up their shifter. They mocked “rinky-dink sticks.” One ad declared that every dragstrip from Indy to Pomona was Hurst Country. George’s creation, The Hurst Floor Shifter became synonymous with speed and excitement.

Dutch made sure those ads promised that with a Hurst shifter, you were in on something special — and you’d beat the guy off the line every time, if only in your imagination.

Postscript:

Hurst ads were my first exposure to Elmore Leonard. At the time, at 12 years old, I was deep into the mythology of car culture — hot rods, customs, and drag racing had me completely enthralled. I was buying Hot Rod and Super Stock, reading them cover to cover, including the ads. I was reading Dutch’s edgy ad prose every month or two, long before I ever knew his name. Just another thread running between us before we ever crossed paths — he took on a world he didn’t know and made it his. Later, as his researcher, I’d bring him other worlds he didn’t know, and he’d make them his too, every time.

Take a closer look at Dutch’s Hurst ads.