In a letter dated February 16, 1972. Dutch’s agent H.N. “Swanie” Swanson wrote in a postscript: “I think you might want to read a new book just published, The Friends of Eddie Coyle by George V. Higgins. Has fine dialogue and underworld characters. Very heavy, as they say on the strip.” Dutch bought it, opened to the first line: “Jackie Brown, at 26, with no expression on his face, said that he could get some guns.” He was hooked.

What hit him immediately was how Higgins told the story through dialogue. The characters did all the work. No setups. No staging. The plot just came out as they talked. Incessant talk — that’s what set Eddie Coyle apart. Higgins led with dialogue. No omniscient author stuck a nose in to disrupt the flow .

Some readers would be totally lost in Higgins word jungle. They were not used to reading without a safety net. But not Dutch, he was set free: “So this was how you do it.” he said with a hint of excitement. .

Dutch was already writing in much the same way as Higgins., “I was already writing in scenes, trying to move my plots with dialogue while keeping the voices relatively flat, understated.” But he was missing some vital something. “What I learned from George Higgins,” Dutch wrote in the Introduction, “was to relax, not be so rigid in trying to make the prose sound like writing…”

“Most of all, George Higgins showed me how to get into scenes without wasting time, without setting up the scene, where the characters are and what they look like. In other words, hook the reader right away.”

Dutch goes on to write that The Friends of Eddie Coyle worked by doing the opposite of reader expectations. It’s a crime novel with almost no crime on the page. You see only what these small-timers see — bluffing, spinning, trying to stay out of trouble. Higgins drops you into a Boston of bank robbers, gun runners, stool pigeons, mafia guys. They’re small, scared, more of a threat to each other than anyone else.

Mostly, it’s talk. Pages of it. Rambling, bluffing, complaining, trying to look tough or buy time.

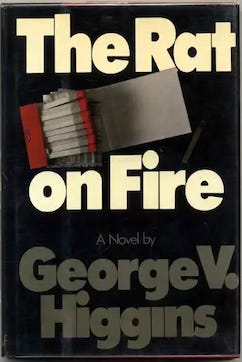

The Rat on Fire, which Dutch reviewed in 1981, centered around a landlord set to torch his own buildings for the insurance, and the cops waiting for it to happen.

Dutch’s take:

“He [Higgins] avoids melodrama in melodramatic situations by letting his characters tell the story. Still, there’s suspense.”

And he added,

“It’s been said as criticism that all Higgins’s people sound alike. Which is fairly true, but not valid as criticism. Why wouldn’t they sound alike? They’re all from the same general area and all pretty much in the same life.”

In 1983, Dutch reviewed A Choice of Enemies, about a state commission trying to pin bribery charges on a crooked Speaker who’s been taking money so long he can’t see what the fuss is about.

Dutch wrote:

“Good dialogue in fiction, designed to move the story, has only the sound of reality anyway; tape-recorder-perfect, it would bore the reader to death.”

In other words, Dutch was saying, dialogue only needs to seem real. If it sounded exactly like real speech, it’d put you to sleep.

Dutch realized that critics and readers often griped about all that dense talk in Higgins. They said his people rambled or sounded alike. But that was the whole point.

Higgins used a truckload of words, but none of them were wasted. He filled the page. There was plenty of white space on Dutch’s pages, but both authors showed you could build a crime novel — or any novel for that matter — on dialogue alone.

Great post on a great book. This--"Dialogue only needs to seem real. If it sounded exactly like real speech, it’d put you to sleep"--in one-hundred-percent true and often overlooked. I once taught Freaky Deaky to a class of college kids and they all loved how "realistic" the dialogue was. When I asked them what they meant by "realistic," they found that question more difficult to answer. It's like how everyone praises David Mamet for the same thing--but (as you know) just inserting four-letter words does not make for great dialogue.