Revisiting My 1980 Review of City Primeval

Forty-five years later, my view of Elmore Leonard’s Detroit classic is unchanged. This is the book that launched Dutch into literary heights and got me my job as his researcher.

Forty-five years ago, a few months before I got my first research assignment for Elmore Leonard, I wrote this review of City Primeval for The Oakland Press, just as the book was being published in the fall of 1980. Looking back, I’m struck by how unchanged my perspective is—what I saw then, I see now: Leonard’s raw prose, his knack for turning Detroit into a living character, and his way of folding Western codes into modern crime. City Primeval stands as a classic.

Tense ‘City Primeval’ is local author at his best

By Gregg Sutter

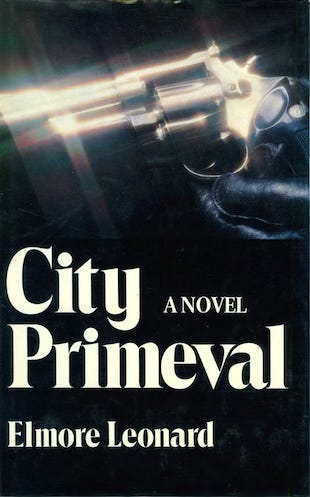

CITY PRIMEVAL, by Elmore Leonard. Arbor House. 275 pages. $10.95.

The ad for Elmore Leonard’s latest suspense thriller, City Primeval, links his name with that of Dashiell Hammett, the master of the hard-boiled detective novel.

The comparison is more than just publisher’s hype: Both men write verbally raw, economical prose; straying seldom from tight, well-drawn stories. Both understand crooks and cops and the gray area in between them. Each can turn the subjects of murder and mayhem into a poetry of violence.

Leonard, for his part, learned the value of lean dialogue writing Westerns in the early 1950s. He impressed critics and editors with a penchant for realism not normally found in this stereotype-laden genre. Hombre (1960), his high-water mark as a Western writer, was recently included in a list of the top 25 westerns of all time.

After a decade and a half of more books (including The Big Bounce and Valdez is Coming) and Hollywood screenplays (Joe Kidd and Mr. Majestyk), Leonard said adios to the buttes and barrancas of his beloved Old West. Instead, he has focused for several years on the concrete canyons of his native Detroit and its suburban haunts, including his present home of Birmingham.

Leonard’s Detroit-based characters are a cast of common people, drowning in serious crime; almost entirely centered around the sin of greed. City Primeval, however, is a departure from Leonard’s other “Detroit books”—Fifty-Two Pickup (1975), Swag (1976), Unknown Man No. 89 (1977) and The Switch (1978). In this newest novel, the author opens with a totally random murder, committed by Leonard’s sleaziest, least-lovable protagonist to date—Clement Mansell, also known as the Oklahoma Wildman.

Clement deserves the nickname. After a night at the Hazel Park race track, he picks out a victim and shadows the man, planning to rob him. Driving down Dequindre, though, Clement loses the man when a big Continental hogs the road in front of him. So, he trades greed for revenge, corners the driver of the Continental and shoots him five times through the sunroof of his borrowed Buick.

A more typical Leonard protagonist would experience some remorse for such a deed but not Clement—he makes the best of any situation; rifling the victim’s wallet and abducting his screaming girlfriend. He figures he’ll force her to give up the dead man’s address so at least he can rob the man’s home and have something to show for the murder.

However, it just isn’t Clement’s night: the girl bolts from the Buick and he has to shoot her too as she scurries down the fairway of the Palmer Park Municipal Golf Course. All this happens by the end of the first chapter. Then Leonard relaxes and has some real fun.

The next morning, Clement reads in a newspaper that the man he killed was a Recorder’s Court judge. He also finds a way to blackmail one of the judge’s female friends. Meanwhile, Clement resumes his search for his original victim, an Albanian. He finds the man, tortures him, and ends up being chased by an Albanian brotherhood.

Of course, Clement’s homicidal handiwork has attracted the attention of the Detroit Police Felony Homicide Unit, Squad Seven, led by a former Texan, Lt. Raymond Cruz. As Leonard spins his tale, Cruz becomes Clement’s other half. Cruz is willing to ignore police procedure in his attempt to handle Clement, in the same way Clement handled the judge. The ensuing conflict is the epicenter of the novel: the lawman and the desperado become just a couple of kids playing with guns.

Leonard has gone full circle. Beneath the facade of a police story rests a simple Western plot. Clearly, there is a thread strung between Leonard’s earlier Westerns and this novel. Even Leonard’s publisher evokes the Western genre by subtitling the book, High Noon in Detroit.

Books aren’t written much more hard-boiled and suspenseful than City Primeval, mainly because Leonard is using his raw prose to tell about real things. He has rendered the most detailed sketch yet of the inner workings of Detroit homicide cops and made Detroit itself a “character” in his story. Many local writers do this, but Leonard does it best. He captures the feel and smell of the area through brisk dialogue and a painter’s eye that transposes city landscapes into hard-edged sentences.

In this reviewer’s mind, Elmore Leonard is one of the few masters of the crime novel today. It’s a mistake, though, to lock him in that category, just as it was a mistake to label him strictly a Western writer 20 years ago. Leonard is simply a tremendous writer. City Primeval is proof.

Thank you for sharing this and him